From the onset of our democracy, it could be argued that the core aim of the country has been the attainment of a socially-just society. This purpose is well articulated in the Preamble of The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa which states:

“We, the people of South Africa, Recognise the injustices of our past; Honour those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land; Respect those who have worked to build and develop our country; and Believe that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity. We therefore, through our freely elected representatives, adopt this Constitution as the supreme law of the Republic so as to -

May God protect our people. Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika. Morena boloka setjhaba sa heso. God seën Suid-Afrika. God bless South Africa. Mudzimu fhatutshedza Afurika. Hosi katekisa Afrika.” |

This is fundamentally important within the South African context, to correct the prevailing social and economic imbalances derived from our Apartheid (and prior) history. Thus, social justice can be seen as ensuring equality for all through equitable access to economic and social development opportunities within South Africa. Yet, for all the progress that has been made over the past few decades, significant socio-economic issues persist and look to get worse in the very near future.

Poverty, Inequality and Unemployment have been stated, by policymakers, as the key components of the problems that hinder our progress towards national development. The Department of Social Development’s Revised White Paper on Families in South Africa goes into significant detail on the social, environmental, and economic setting that South African households find themselves within. It is estimated that 55% of the population lives within the Lower-Bound Poverty Line (LBPL) of R890 per month. In terms of inequality, the white paper indicates that South Africa’s Gini coefficient lies between 0.65 and 0.68 while the International Monetary Fund shows that South Africa's Gini coefficient is highest amongst emerging markets (and is growing while other markets are reducing income inequality).

Finally, unemployment remains a significant and stubbornly consistent concern. According to Statistics South Africa, the unemployment rate was at 34.5% (in the first quarter of 2022) – this has been increasing for the past decade. Additionally, the youth unemployment rate stood at 42.1% for those aged between the ages of 24-34 years. The Department of Social Development’s Revised White Paper on Families in South Africa suggests that this is one of the major causes of sustained inequality and poverty in the country. It is clear to see that a lack of economic participation and development within the population increases the probability of undesired social outcomes and hinders the achievement of social justice and social cohesion.

The Government’s Medium Term Strategic Framework (MTSF) indicates the targeted outcomes of government policy and interventions across the areas discussed above.

Table 1: MTSF Targets and Consideration around Poverty, Inequality and Unemployment

| Themes | Targets | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Unemployment | 2 million jobs to be created for the youth between 2019 and 2030 | The President indicated, in the 2022 SONA, that the government must create an enabling environment for businesses to invest, grow and absorb labour. Measures are being put in place to reduce bureaucracy and turnaround time for businesses to be compliant to operate. |

| Inequality | A Gini Coefficient of 0.66 by 2024 | Inequality is deeply entrenched within our country and further promotes the separation of groups and communities which limits nation-building. Job creation, per capita economic growth, as well as equitable income taxing and distribution mechanisms, are required to address this challenge. |

| Poverty | An LBPL rate of 28% by 2024. | Increasing the employability and competitiveness of South Africans and their businesses is essential, whilst enabling equitable access to opportunities for development and economic participation. |

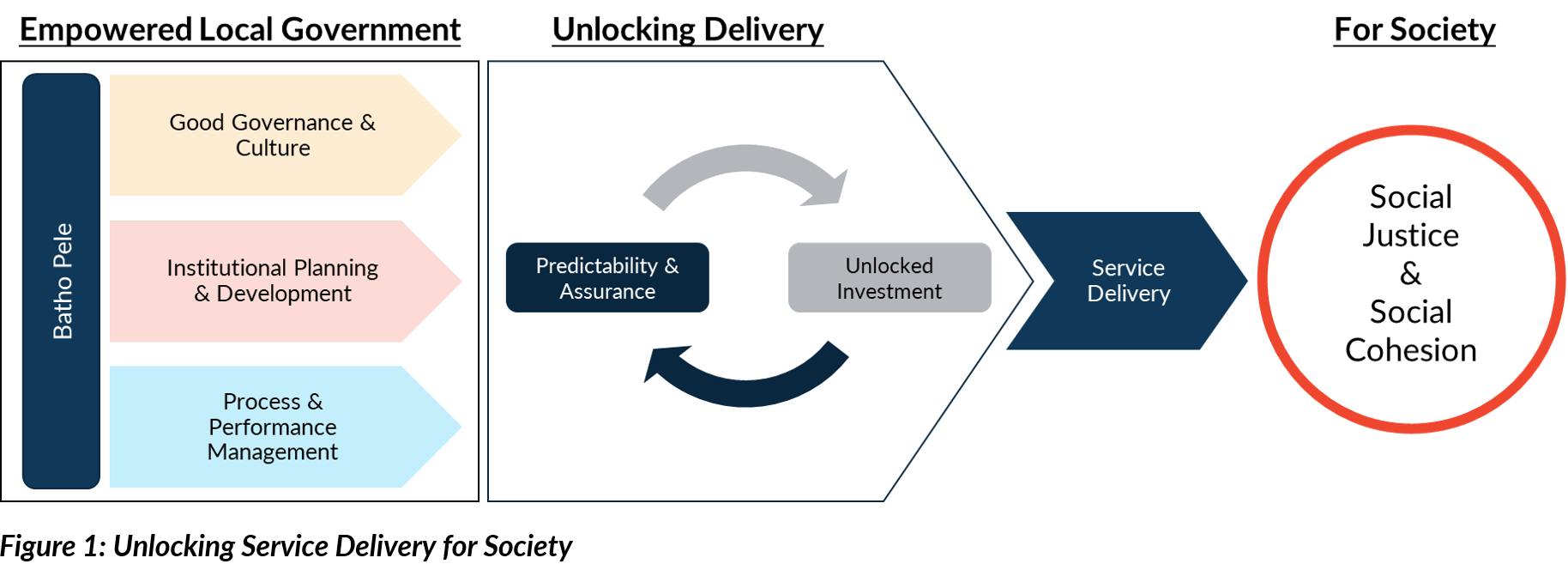

Essentially, economic growth and programmes that drive economic inclusion are fundamental to resolving issues of Poverty, Inequality and Unemployment and this article seeks to establish the important role of Local Government within this process. This does not mean that the government is solely responsible for driving change but must be seen to lead and integrate society towards this common goal. The figure below summarises the perspective of the author from a value chain perspective.

Service Delivery

Chapter 7 of the South African Constitution establishes Local Government and states that it consists of the municipalities that cover the territory of the country. Specifically, section 152 of the Constitution provides five core objectives of Local Government as stated below:

- to provide a democratic and accountable government for local communities;

- to ensure the provision of services to communities in a sustainable manner;

- to promote social and economic development;

- to promote a safe and healthy environment; and

- to encourage the involvement of communities and community organisations in the matters of local government.

From these objectives, it is clear that municipalities play a significant role in creating and sustaining an environment for social justice and social cohesion through their service delivery. In terms of income and wealth creation, the services provided by Local Government also establish a critical foundation for much needed social and economic activity. Safe, hygienic and productive spaces raise the quality of social and economic interactions. Section 156 of the Constitution further indicates that municipalities have the executive authority of the functions listed in Part B of Schedules 4 and 5 of the Constitution as indicated below. Several basic services (i.e. energy reticulation, water, sanitation and refuse removal) that are fundamental to creating a safe and productive environment are also included within this list of functions.

Table 2: Local Government Functional Areas

| Schedule 4, Part B | Schedule 5, Part B |

|---|---|

|

|

The Constitution, as well as legislation[1], further articulate the conditions and processes of assigning or adjusting the functions of municipalities according to capacity and other constraints. It is largely through these functions that service delivery projects and programmes are delivered by municipalities, with support and coordination from the National and Provincial spheres of Government.

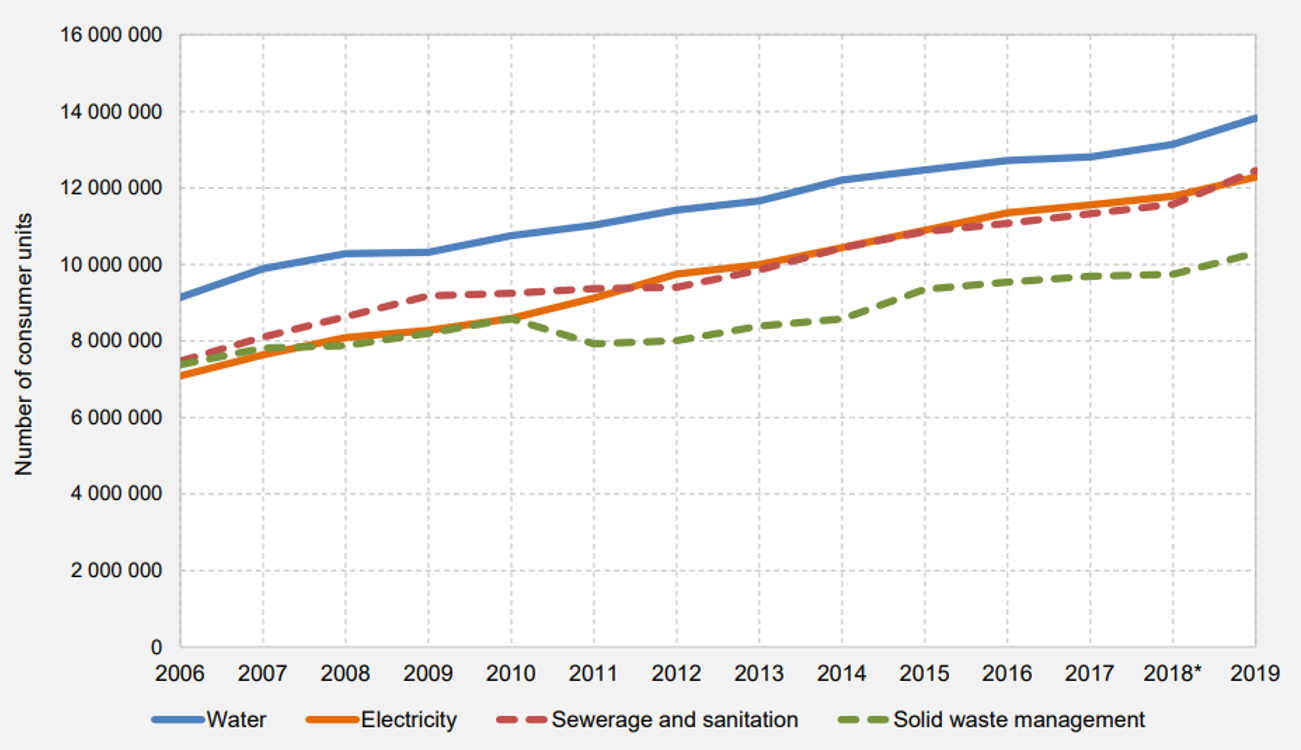

One of the key issues concerning service delivery is that the demand for services from municipalities has outpaced the availability of supply. Demand is largely driven by the growth in the population and the volume of economic activity, while supply is enabled by community services, infrastructure development and maintenance, as well as public engagement. From a demand-side perspective, the need for basic services is growing as communities develop (see figure below). Additionally, between 18 and 23% of households are receiving some form of free basic service. Although this trend has been decreasing over the past few years, persistent unemployment and poverty risk an increased reliance on this support if the economy struggles to grow and grow inclusively. Furthermore, the growth of informal settlements around urban areas is pushing electricity reticulation, environmental hygiene and water provision to its limits, despite the best efforts of some municipalities to cope with this growth in demand.

________________________

[2] Municipal Structures Act, Municipal Systems Act, Municipal Financial Management Act

Figure 2: Number of consumer unit receiving basic service (2006-2019)[1]

From a supply-side perspective, data from the Construction Industry Development Board’s Compliance Monitor shows a consistent trend of underspending on planned infrastructure projects, which bottlenecks municipalities’ service delivery potential. As an example, over the course of 2020 and 2021, only 20-30% of advertised infrastructure tenders notices were in fact awarded by municipalities. It must be acknowledged that it would be difficult for developmental programmes to occur effectively within communities without sufficient basic delivery that creates an enabling environment.

In both the 2022 State of the Nation Address and the 2022 National Treasury Budget review, infrastructure development was highlighted as a key lever for driving economic growth over the next 3 to 4 years. The national budget forecasts an acceleration of growth in Gross Fixed Capital Formation which will largely be driven by investment in infrastructure. A significant proportion of the budget for infrastructure is allocated to Local Government within the Medium Term Expenditure Framework and will likely grow going forward. Thus, the internal systems and processes of municipalities need to be adequately capacitated to allocate and utilise these resources effectively for improved service delivery outcomes.

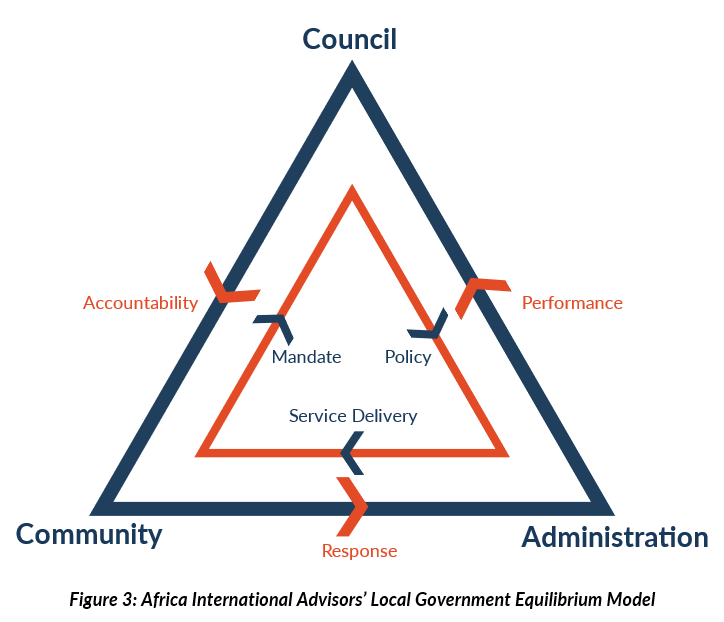

From an internal perspective, much has been said about the state of governance and service delivery effectiveness within Local Government. This is certainly an undesirable situation and does require the coordinated efforts of government and the public to be addressed. Ultimately though, service delivery is the outcome of good governance and a culture of accountability amongst the core stakeholders of Local Government, i.e.

- The Community

- The Council

- The Administration

The Municipal System Act details the rights, powers and duties of all three stakeholders within the system of Local Government, and also provides for key decisions and actions that are taken by these stakeholders within the periphery of legislation. From both the engagements that we have had with municipalities and the trends

__________________

[3] Statistics South Africa, Non-Financial Census of Municipalities, 2019

that we have observed over the years, it has become clear that service delivery is but one component of the interactions and transactions that Local Government stakeholders have with each other, and the broader national community. Service delivery is an important outcome of an effective municipality but requires an equilibrium of forces and interactions across the board to be realised. Otherwise, the system becomes unstable which eventually shows from a service delivery perspective as that tends to be the most tangible indicator of the effectiveness of a municipality. The finer details of this perspective will be shared in later publications. Suffice it to say, that the quality of service delivery within municipalities is not solely dependent on the effectiveness of a municipality’s Administration, but also the decision and actions of the Council and Community of the municipality as well.

Unlocking Service Delivery

As discussed, municipalities provide many important services to the communities within their jurisdiction. To this end, the development and roll-out of service delivery modelling tools for Local Government by the Department of Cooperative Governance (DCoG) is an important step toward systemising service delivery planning and its capacitation through organisational development. The Local Government Guidelines for the Implementation of the Municipal Staff Regulations elaborate on the design and application of the DCoG’s Service Delivery Model Framework. The framework both demonstrates and groups the key capabilities that are required for a municipality to fulfil its Constitutional and Legislative functions. This creates a standardised approach to modelling service delivery from the aspirations and goals of a municipality’s Integrated Development Plan (IDP) and Service Delivery Budget Implementation Plan (SDBIP). Service Delivery Modelling is an extensive process of analysis and consultation; a few key components, that lay a good foundation for the development of a good service delivery model, are indicated below.

Table 3: Key components to Service Delivery Modelling

| Components | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Mandate Analysis | Define and confirm the municipality’s mandate. This is essentially derived from the Constitution, Legislation and Policy (across all three spheres of government). Often, this process is conducted in detail in the development of an IDP and annual SDBIP, but it is important to clarify the functions and expectations of the municipality from a service delivery perspective by analysing the mandate. |

| Service Beneficiaries and Actors | Confirm the service beneficiaries of the services that lie within the mandate. It is to the municipality's benefit to have robust intelligence on the stakeholders it serves, and how their needs are evolving, to inform service delivery planning. Additionally, contributors to the delivery of services (both internally and externally) must be indicated with clearly defined expectations and constraints. |

| Services | Collate and describe the services that the municipality is mandated to perform. This includes the scope and quality of service that can be expected in line with the mandate of the municipality. Also, consider the municipality’s service delivery commitments as indicated in the IDP and SDBIP as well as the resources that are available to perform the required services. |

| Service Delivery Method | Describe the current method of service delivery and unpack the processes that convert capital into the provision of services. Collate intelligence of how this delivery has performed currently and in the past. |

| Analyse | Review the efficiency and effectiveness of the municipality’s delivery. Reflect upon the processes that drive service delivery as well as the operational environment:

Also consider sections 78 to 84 of the Municipal Systems Act. |

| Preferred Delivery | Develop alternative options for improvement and systematically filter for those which are implementable by the municipality. Plan for their implementation and ensure that a performance framework is in place to enable oversight and continuous improvement. Communicate this to the community and other affected stakeholders so that expectations can be managed appropriately. |

Service delivery modelling does not guarantee success. Rather, it improves the probability of success by applying a systematic approach to service delivery planning and managing service delivery risk during execution. As far as possible, it creates an atmosphere of predictability in an uncertain environment. That is; although the environment may shift, the municipality has clearly defined, implemented, and controlled systems to deliver upon its mandate.

This is important because service delivery requires investment and investment requires some degree of certainty and incentive. The national budget review clearly articulates the importance of the private sector in achieving a 30% investment to GDP ratio by 2030, as indicated in the National Development Plan. Furthermore, the fiscus is stretched, thus capital will need to be raised outside of government to close the funding gap. However, the current fiscal and governance landscape within Local Government does not do much to persuade private capital to invest robustly in its infrastructure, as much as the need for investment is well recognised. Currently, the risk is simply too high. This does not mean that there are no successfully implemented public-private partnerships within Local Government, just that there is a significant opportunity to unlock broader investment if the environment is one that engenders trust from its community and potential investors.

Many municipalities globally attract direct investment and issue municipal bonds to capitalise investment into infrastructure and development within their area. In South Africa, the City of Johannesburg has a retail bond programme which is accessible through the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, where individuals can invest a minimum of R1,000 to earn a return. This capital funds the development of city spaces and infrastructure to create a vibrant city that brings people closer to where they work and play. The accessibility also enables a broader spectrum of the local population to contribute and then benefit (both economically and environmentally) from their participation. This is wealth creation at a community scale. It is tangible and direct because it is local. It brings communities together and accelerates the cohesiveness of society. Consider the impact if such programmes were widespread throughout the country; complemented by targeted commercial and developmental investments to accelerate inclusive economic growth and social development.

This is an achievable prospect if municipalities can provide predictability and accountability to its stakeholders for the resources that they are entrusted with. Predictability enables trust which assists in unlocking investment for service delivery whilst delivering returns (both financial and non-financial) to investors. That return and its assurance is critical to achieve a virtuous cycle that self-sustains development and growth within the ecosystem of a municipality. This would require an empowered Local Government with deep multilateral cooperation and good governance.

Empowering Local Government

There is significant potential within Local Government that requires an enabling institutional environment. This environment is well depicted in section 195 of the Constitution which describes the values and principles that should govern the public administration, including the Administration within Local Government. These values are underpinned by the principle of “Batho Pele” (i.e. “The People First”), as articulated in the Department of Public Service Administration’s White Paper on Transforming Public Services Administration. In the preamble to our Constitution, it states that we as South Africans should aim to “Improve the quality of life of all citizens and free the potential of each person”. Many socio-economic indicators point to the need for urgent focus on the development of our society, particularly in how we may allocate resources and execute upon our projects and programmes.

The current Councils of our municipalities were elected during outcries for improvement in a declining state of service delivery. They have the power and opportunity, as the elected legislative and executive authorities of their municipalities, to set policy and strategic direction within the municipality. Councils also appoint the senior management of the municipality and oversee the execution of its mandate. Well-informed decision-making and active public participation are crucial to both guide the efforts of the Administration and meaningfully engage and consult the community. Many tools, frameworks, programmes, and projects have been developed and implemented to enable good governance and performance across all spheres of government. Ultimately, good governance is about ethical decisions followed by appropriate behaviours that shape the culture of the institution. Additionally, prioritisation is crucial as it is impractical for municipalities to be all things to all people. This is further conflated by the need to respond to various (and numerous) mandates that sometime compete for resources or should be championed by other spheres of government. Community engagement (which from this perspective also includes government stakeholders) should enable an appreciation of the finite resources of the municipality and establishing an agreed expectation of service delivery. Where this agreement is established, it is if of the utmost importance that all stakeholders follow through on their commitments and contribution to avoid a loss of trust and credibility.

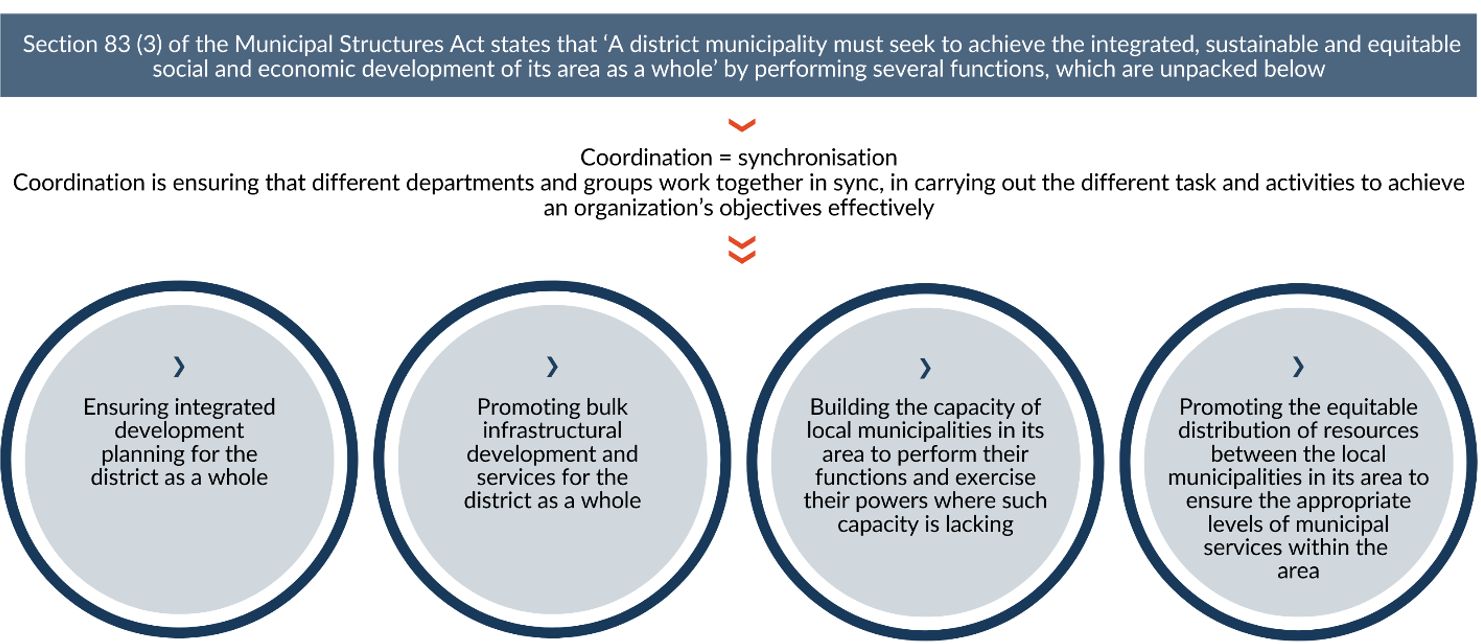

Local Government has a robust Integrated Development Planning process which involves a significant degree of consultation and analysis. This is to ensure that the mandate is translated into actionable priorities for the Council and Administration of the municipality. The recent implementation of the District Development Model saw the development of the first generation of the “One Plan” as a part of municipalities’ IDPs. The One Plan integrates planning across all sectors and spheres of government within the geography of each District Municipality and Metropolitan, to ensure that infrastructure planning is effective and well-coordinated. An exciting prospect of the District Development Model is the creation of District hubs that embrace information technology, digitalisation, and technical expertise to capacitate planning and service delivery within Local Government through regional economies of scale. Section 83 (3) of the Municipal Structures Act highlights the importance of the coordination role that District Municipalities play in ensuring equitable service delivery to the local municipalities in their region. District Municipalities have the potential to:

- Integrate planning for an entire region within its geography,

- consolidate economies of scale for regional infrastructure development,

- serve as centres of excellence for service delivery capacitation, and

- facilitate Local Government cooperation and resource sharing within their regions.

Figure 4: Coordination functions of District Municipalities

This requires District Municipalities that have the tools and expertise to add value to Local Municipalities where required. It also requires good relations between District and Local Municipalities as envisaged by the Intergovernmental Relations (IGR) Framework Act. Ideally, beyond regular IGR forums, District officials should be engaging with their counterparts in Local Municipalities, at a tactical level, to develop integrated responses to emerging service delivery issues or opportunities on an ongoing basis. This requires alignment across all levels, including senior management and the political office bearers within a district so that officials feel empowered to work constructively together.

Section 77 of the Municipal Systems Act indicates the triggers for a Service Delivery Modelling process. One of them is the election of new Councils and the appointment of Municipal Managers. Another is a review of IDP and SDBIP. Thus, it is necessary for all municipalities to review their Services Delivery Models annually to demonstrate the execution that will achieve the targets of their SDBIPs. In conjunction with the Local Government Guidelines for the Implementation of the Municipal Staff Regulations, municipalities should ensure that options for the methods of delivering services are profiled extensively, assessed, and turned into a road map of action with measures of success.

With the Service Delivery Model completed, the Operating Model of the Municipality must be developed to capacitate service delivery. All relevant forms of capital should be considered, accounted for, and allocated to the functions of the municipality. DCoG gazetted Local Government Municipal Staffing Regulations in 2021 which regulate the management and development of a municipality’s most important asset: its people. A competency framework has also been provided within the regulations, to inform on the competencies required to capacitate each of the identified capabilities in the Service Delivery Model of a municipality. It also disaggregates levels of experience and proficiency across different levels within a profession, which can serve as a foundation for career development planning. The application of these tools will ensure that the right roles are developed within the organisational design of the municipality and that they are capacitated with the right people to perform. To this end, it is important that municipalities have capable Organisational Development professionals and Human Capital professionals that are trained and empowered to facilitate the Service Delivery Modelling and Organisational Design process, under the auspices of the Municipal Manager. They should also work closely with Performance Management and Municipal Planning professionals to provide information that can aid the process. It is also important that as many stakeholders as possible within the Administration are involved in this process so that change management can begin from the conceptualisation of the service delivery model.

Finally, the service delivery model of the municipality must have well-defined processes that can be monitored effectively. Generally, it is the responsibility of those who are in management to ensure that systems are in place to account for the performance and the productivity of the capital invested towards service delivery. Chapter 4 of the gazetted Local Government Municipal Staffing Regulations has defined the required activities and scope for performance management within Local Government. It is expected that performance management will need to disaggregate performance expectations from the IDP and SDBIP into performance measure across all departments, functions, and employees (or teams). This will ensure that the contributions of the work towards the municipality’s goals are accounted for. Additionally, robust performance management can guide skills development planning within the municipality. This can expand the impact of skills development spending whilst also adding to the employee value proposition of the workforce by empowering them to act effectively within their roles.

The advent of the fourth industrial revolution has enabled the digitalisation of business processes and provided access to real-time information for performance measurement. Often, services involve some degree of transactional or routine tasks, with turnaround times ranging from seconds to days or even weeks. However, digitalisation must be built upon a foundation of business processes that are effectively designed and respond to the requirements of the Service Delivery Model. From an Organisational Design perspective, effective business processes fast track the development of meaningful and outcome driven Job Descriptions. The content of the Job Descriptions should be informed by the value that the incumbent contributes within the processes of service delivery. From this perspective, Job Descriptions can be viewed as a role specific transformation of functionally specific business processes.

Conclusions

The first thing that needs to be in place is conscious, ethical and decisive leadership within the Council and Administration of the Local Government system. Significant powers are afforded to the leadership within Local Government and these should be exercised for the benefit of the Community, without fear or favour. This includes the recognition of high performance as well as consequence management and/or capacity building for low performance. This requires the development and frequent review of the artefacts that demonstrate good governance and control in the municipality. These include policies, business processes, standard operating procedures, service standards and delegations of authority. These tools should be used to develop an enabling culture for service delivery within the municipality. Additionally, communities need to constructively participate in governance processes through public-participation opportunities. Neither a silent nor a disruptive community can hope to sustainably steer the direction of a municipality’s projects and programmes for their benefit.

Secondly, there needs to be a robust capacitation of organisational development within municipalities. Organisational Development practitioners need to be skilled in using the Local Government Guidelines for the implementation of the Municipal Staff Regulations. Every municipality needs to have a Service Delivery Model, documented, and monitored workflows and fit-for-purpose organisational structures. Additionally, management needs to heed the expert guidance provided by Organisational Development practitioners in their deliberations to ensure that the municipality’s structure is compliant and fit to respond to service delivery commitments. Where there are opportunities to use digitalisation to improve transparency, oversight and productivity, business cases should be developed to assess the pro and cons of the various solutions that are available. Preference should also be afforded to locally developed solutions to fulfil the localisation imperatives of government policy.

Lastly, municipalities need to implement robust performance management and demonstrate predictability. Beyond the fact that this is now a legislated requirement going forward, it is a rational requirement to drive an internal culture of performance in municipalities. Even if there are supply side constraints, it is important for Local Government to demonstrate that it is making the best use of the resources at its disposal towards achieving tangible service delivery outcomes. This will improve confidence in our municipalities and lay solid foundation for attracting investment. To this end, Human Capital Management, Performance Management and Line Management functions need to work closely to develop and implement compliant performance management systems within each municipality.

Sep 2022 south africa local government social justice social cohesion human settlements